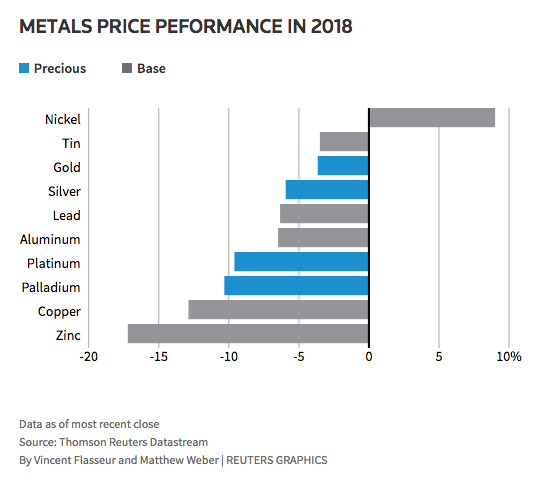

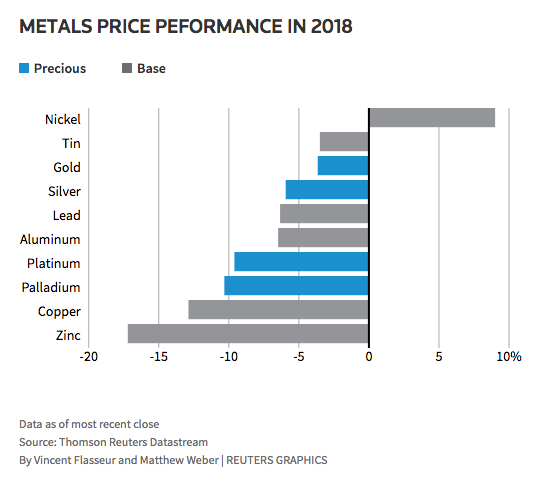

After a gravity-defying run, nickel has now also succumbed to weakness in the industrial metals complex as global trade fears mount, declining to $14,125 per tonne on Monday.

The metal, mainly used in stainless steel manufacture, is down 10% or more than $1,600 a tonne from more than three-year highs hit on the LME a month ago.

Nickel is still up by 62% compared to its June 2017 lows, mostly on the back of falling inventories in top consumer China. On the Shanghai Futures Exchange nickel stocks have dropped for 24 straight weeks while LME warehouses are the emptiest since mid-2014.

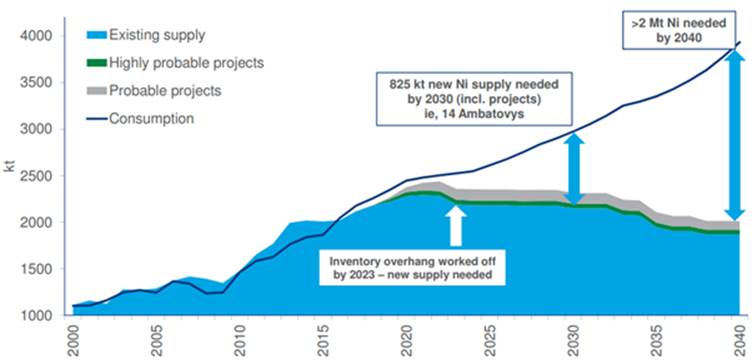

And recent weakness has not altered a bullish longer term outlook for nickel with industry research house Wood Mackenzie adding its voice to the plus-column in a note out on Monday.

And recent weakness has not altered a bullish longer term outlook for nickel with industry research house Wood Mackenzie adding its voice to the plus-column in a note out on Monday.

While stainless steel production – currently nearly 80% of total demand for nickel – is expected to stay solid over the coming years, booming demand from the electric vehicle battery market is set to fundamentally alter the structure of the industry.

Michael Sinden, WoodMac Research Director, and Senior Research Analyst, Rory Townsend say in their long term outlook for nickel that demand for nickel in EV batteries will contribute 1.26 million tonnes to nickel demand in 2040.

China’s nickel pig iron production fed from Indonesian and Philippine mines dominate the industry currently, but producing battery grade material from Class 2 nickel is prohibitively expensive

That compares to total primary nickel production last year of not much more than 2 million tonnes.

Slightly more than half the total is from so-called Class 1 producers which is suitable for conversion into nickel sulphate used in battery manufacture. Class 1 nickel powder for sulphate production enjoys a premium of as much as a third over LME reference prices, but for miners to switch to battery grade material requires huge investments to upgrade refining and processing facilities.

China’s nickel pig iron production fed from Indonesian and Philippine mines dominate the industry currently, but producing battery grade purities from Class 2 sources like NPI is prohibitively expensive.

Chinese battery makers stocking up on high-grade material helps to explain why the nickel price has stayed healthy despite looming oversupply in the NPI industry and is likely also behind the rapid drawdown stocks on exchanges, which are of Class 1.

Finding enough nickel raw materials for battery-sulphate producers “is likely to be a considerable challenge post-2025” according to WoodMac and the firm has a price prediction to match the anticipated supply problem:

The nickel market starts to need additional nickel from unidentified resources in 2023, we envisage prices reaching an annual average peak of US$28,700/t by 2022.

Source: Wood Mackenzie

Nickel, manganese and cobalt (NMC) batteries are favoured by most of the world’s automakers and the industry is hard at work to reduce pricey cobalt loadings in favour of greater use of nickel.

Light passenger EVs using batteries with a 8:1:1 NMC ratio, which should become widely deployed over the next decade, require roughly 52 kilograms of nickel. Last year 3 million battery electric vehicles were sold. By 2025 battery electric vehicles could reach nearly 15 million unit sales with plug-in hybrids accounting for an additional 10 million vehicles.

The post Electric vehicle demand will double nickel price – as soon as 2022 appeared first on MINING.com.

Source: Mining.com