What’s the best way to deal with a teacher who comes into your school and starts threatening all the other teachers? Well if you’re Liberal party leader, and Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, the answer is to lecture the bullying teacher about how his approach isn’t the way to get along with all the other teachers. If you’re the bully, you’re not going to listen to that, and instead, will react to the head teacher’s scolding by insulting him, or maybe putting him in a headlock. If that doesn’t work in getting your way, you could try to turn the other teachers against each other, dealing with them separately instead of with the whole teaching staff. “Divide and conquer” works well for bullies.

This little analogy is how we might look at the way Donald Trump has manipulated Canada and Mexico into a situation where not only have they failed to recognize and counter a typical Trump “art of the deal” strategy in coming up with a renewed tri-lateral trade agreement, but where the two countries may now be forced to negotiate separate trade deals with their largest trading partner. How did we get here and what does this ratcheted-up trade war mean for Canada, the United States and investors? This article will address these questions.

NAFTA 101

The North American Free Trade Agreement came into force on January 1, 1994. The agreement was negotiated by then-President George H.W. Bush, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari. It superseded the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement between the US and Canada, signed in 1988. The goal was to eliminate trade barriers between the three nations. When it was passed in ‘94 it eliminated tariffs on over half of Mexico’s exports to the US and more than a third of US exports to Mexico. Within 10 years all US-Mexico tariffs were to be eliminated except for some American agricultural exports which would be phased out over 15 years. Most of the trade between the US and Canada was already duty-free. An important part of NAFTA is Chapter 52, the dispute resolution mechanism, which allows for the settlement of trade conflicts through a panel of adjudicators including retired judges.

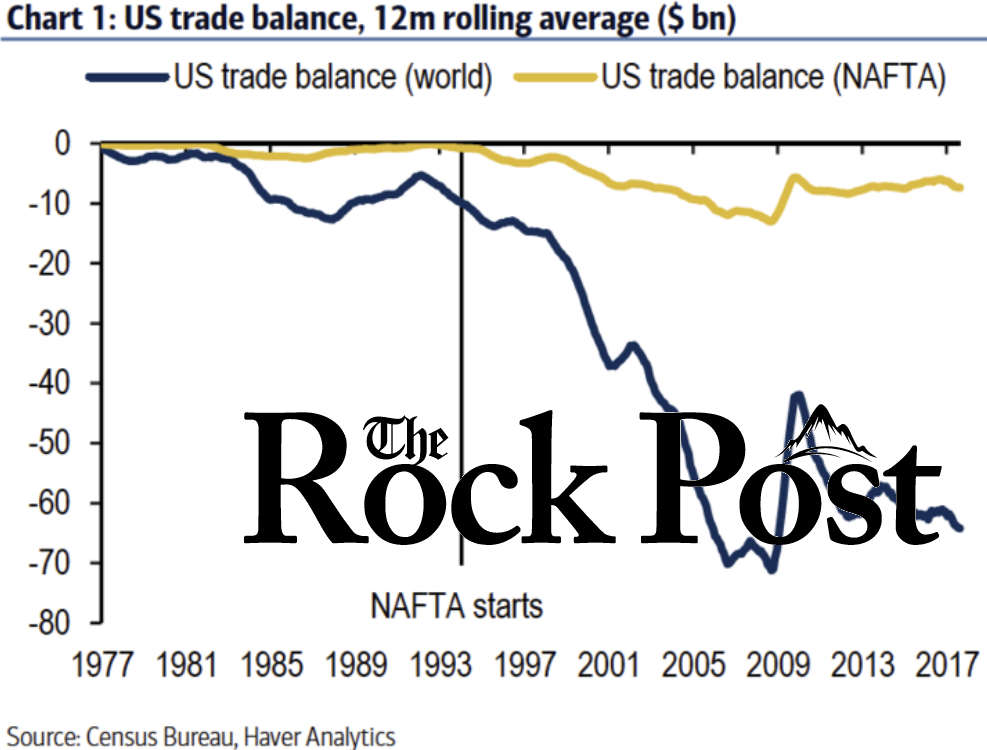

As to whether or not NAFTA has been good for the economies of the signatories, the record is mixed. A 2015 study concluded that intra-bloc trade increased by 41% for the US and 118% for Mexico, but only 11% for Canada. Controversially, assembly plants that imported components and produced goods for export, known as “maquilladoras”, sprung up in northern Mexico and bled jobs from the United States. While Mexico has done well from NAFTA, through for example increased production of meat and corn, and growing its middle class, Mexico’s welfare rate has gone up.

The US Chamber of Commerce credits the agreement with increasing trade in goods and services from $337 billion to $1.2 trillion between 1993 and 2011, but the AFL-CIO (the largest federation of US unions) blames it for shedding 700,000 jobs to Mexico during that time-frame.

When then-US presidential candidate Donald Trump hit the campaign trail in 2016, one of his biggest complaints was NAFTA, which he called “the worst trade deal the US ever signed.” He riffed on the unions’ argument about lost jobs to Mexico, citing companies such as Ford and Carrier, an air-conditioning firm. Trump went so far as to say he would “tear up NAFTA”, which caused widespread consternation among both Democrats and Republicans – the latter traditionally free-traders – and politicians and business leaders in Canada who generally regard NAFTA as a success. Messing with NAFTA is also seen to be like “trying to get the horse back into the barn, after the barn door has been closed,” since so many supply chains between the US and Canada are inextricably linked.

Not long after becoming President, in January 2017, Trump started the process of renegotiating NAFTA. At first the agreement was to only be “tweaked”, but as the number of meetings between negotiators grew, the process has become more drawn out and fraught with difficulties. US, Mexican and Canadian trade reps have been meeting almost continuously since April, because Trump has insisted he wants a deal before the Mexican general election in July and the US mid-term elections in November.

The main stumbling blocks to a renewed NAFTA are:

- Automotive content: the US wants to increase to 75% from 62.5% the amount of content from one of the three NAFTA partners a North American vehicle must have to be shipped duty-free.

- Chapter 19, a bi-national dispute settlement process for challenging anti-dumping and counter-vailing measures. The US wants to eliminate anti-dumping panels.

- The US wants to restrict government procurement contracts for Mexico and Canada.

- A “sunset clause”. The United States wants a clause that could kill a new NAFTA after five years, but Canada says such a clause is a deal-breaker because it would inject business uncertainty and drive investment away from Canada.

The tariffs

Complicating the completion of a NAFTA deal are the steel and aluminum tariffs that the Trump Administration first threatened to slap on all imports of steel and aluminum earlier this year, then exempted certain countries temporarily, including the EU, Canada and Mexico. The tariffs were due to national security concerns that those imported products were having on American domestic industries.

However in May Trump removed the exemptions, meaning that Canada, Mexico and Europe would all be subject to 25% tariffs on steel and 10% on aluminum.

Canada responded by threatening to impose retaliatory tariffs on $16.6 billion worth of US goods, effective July 1. The list of 100 items includes 25% tariffs on US steel and 10% on consumer good including ketchup, dishwater detergent, toilet paper and washing machines, says a report from The Toronto Star.

Separately, the United States and China are also promising tit for tat sanctions, about $150 billion worth on each side, though they haven’t gone into effect yet.

Trump vs Trudeau

According to a timeline of the NAFTA talks presented by Bloomberg, Trudeau and his team of negotiators led by Chrystia Freeland, his Minister of Foreign Affairs, tried to pass a “skinny” NAFTA deal that would keep most of the deal intact including about 30 chapters completed so far. The idea was to get a deal quickly before the June 1 deadline in order to skirt the metals tariffs. But things went off the rails during a testy phone call between Trump and Trudeau, where Trudeau reportedly balked at Canada being roped into the tariffs on “national security” grounds, to which Trump responded, “Didn’t you guys burn down the White House?” referring to the War of 1812.

Trudeau, Trump and Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto were supposed to meet at the White House to finalize NAFTA, but that meeting was scrapped, according to Trudeau, due to the sunset clause provision, which would cancel NAFTA after five years unless all three countries agreed to extend it. In an interview with NBC News, Trudeau accused the Trump Administration of “trying to divert business investment from Canada to the United States … saying no investor would inject capital in this country if they feared Canada’s preferential access to the massive U.S. market could be disrupted within half a decade.”

“What company is going to want to invest in Canada if five years later there might not be a trade deal with the United States?” he told interviewer Chuck Todd.

A senior Trump advisor who saw the NBC News interview said that Trudeau was blowing the dispute out of proportion, calling it a “family quarrel” between neighbors. “I think he’s overreacting,” White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow said of Trudeau’s comments.

What many have missed in this polemic between Trump and Trudeau is that this is classic Trump “art of the deal”. A billionaire businessman, Trump cares less about diplomacy and politicking than getting a deal done. If that means breaking a few fingers on the other side along the way, so be it. Trudeau, on the other hand, is the consummate politician, always concerned what others will think, carefully couching his words, and generally coming across as smug and condescending to his American counterparts. The same goes for Chrystia Freeland, a former journalist and academic who has never before worked in the business world of Trump and his key advisors.

The Americans have made it clear that a NAFTA deal and the threat of tariffs are closely linked. Here’s what Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative, said in March, commenting on the slow pace of negotiations. “In my view, [the tariffs] are an incentive to get a deal,” he told reporters in Mexico City.

But Trudeau and Freeland apparently didn’t get the memo – or more likely, failed to see what Trump was doing. He wanted a NAFTA deal in order to please his base, which has seen few successes so far in his presidency, except for a continued strong economy (low unemployment, healthy stock markets), and corporate tax cuts, which have mostly gone into massive share buybacks. He’s failed to build a wall, get a deal on health care, or do an immigration overhaul, with Congress deadlocked over DACA – legislation that prevents hundreds of thousands of young, undocumented immigrants from being deported.

Instead, the Canadian pair of Liberals took to berating the Trump Administration. Trudeau told NBC he finds it “frankly insulting” that Trump imposed tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum, saying “that is not how close allies should treat one another.” Trump could care less. His job is to bat for Team America.

Freeland chimed in, appearing on CNN to tell American viewers, “I would just say to all of Canada’s American friends… Seriously: Do you really believe that Canada, your NATO allies, represent a national-security threat to you?”

They will apparently challenge the US tariffs under NAFTA and the World Trade Organization, which is the equivalent of asking the principal to solve a dispute when two teachers can’t agree.

Somebody ought to tell the both of them that the tariffs were never about national security, but rather, were a negotiating tactic to get a better deal on NAFTA. The US wanted more control over the deal in future, rather than shackling itself to an agreement that would be near-impossible to change later, and while Trudeau has a valid point about a sunset clause causing some worry among the business community, it should not have been the hill he chose to die on. Which is what has happened. Now Trump is musing about concluding separate trade deals between the United States and Canada, and the US and Mexico. Meanwhile, NAFTA negotiations have ground to a halt. Steel and aluminum tariffs are in place.

All Trudeau had to do was agree to a sunset clause and the tariff exclusions would have been extended. It was a negotiating tactic, dummy. The Americans told you so. But Trudeau and Freeland don’t have the business backgrounds to handle Trump and his hard-nosed team of NAFTA negotiators. Clearly they didn’t read The Art of the Deal.

Mexico fights back

The original target of the NAFTA re-negotiation was Mexico; it was American jobs fleeing to Mexico that really stuck in Trump’s craw, not trade squabbles with Canada. Now Mexico has been forced to take retaliatory measures against the metals tariffs. The “third Amigo”, a reference to the three leaders of the NAFTA trio when relations were friendlier, has said it will hit the US with 15 to 25% tariff on US steel, a 20% tariff on US pork, apples and potatoes, and up to 25% duties on cheese and bourbon.

It must have given the Mexican president some pleasure to have the opportunity to fire a symbolic shot across the border while Trump is still planning on building a wall to keep illegals out. The Mexican tariffs are likely to hit American farmers the worst, particularly in Minnesota and Iowa, with the latter being the top pork-producing state in the US and Mexico its main export market.

Threats to Canada

What do stalled trade negotiations and the steel and aluminum tariffs mean for Canada? An Ohio-based trade lawyer has said that continuing uncertainty over the NAFTA renegotiation has dampened enthusiasm for investment in Canada, while a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for Economics, in Washington, was quoted saying US tariffs will cost Canada $3.2 billion a year. Canada is the number one steel exporter to the United States, so there is bound to be fallout.

Bloomberg reports that producers of everything from farm equipment to the makers of steel oil pipelines are nervous. The article states that nearly every piece of equipment for grain bins or livestock handling has steel or aluminum in it. Canada exported some C$1.9 billion worth of agricultural equipment in 2017, with 80% going to the US. Montreal-based Rio Tinto Aluminum is the biggest supplier of the lightweight metal to the US, exporting around 1.4 million tonnes to the US annually.

The list of Canada’s retaliatory tariffs shows that metals aren’t the only thing on Canada’s radar. Nothing says Canada like maple syrup, and Quebec producers of the Canadian pancake topping are going to enjoy more protection come July 1st. The proposed tariff on maple sugar and syrup will mostly affect producers in Maine, which formed three-quarters of the C$16.9 million worth of those goods Canada imported in 2017.

Threats to the US

According to a report released Tuesday by Washington-based The Trade Partnership states that 400,000 jobs could be lost from the tariffs in the US. Surprisingly, the majority of job losses will be in the services sector, states the report, due to people who lose their jobs reducing their spending on services. Other sectors likely to feel the pain are agriculture, manufacturing and energy.

Former Canadian prime minister Paul Martin compared the US steel and aluminum tariffs to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act passed in 1930. CBC reminds us:

That law — intended to protect American farmers and manufacturers — raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to their second-highest levels in 100 years. Many historians and economists blame Smoot-Hawley for triggering a cascade of counter-tariffs around the world, strangling trade and worsening the Great Depression — which gave rise to social unrest, isolationism and nationalist movements globally.

“If you take a look at the United States, the number of people who are affected, whether they be farmers, whether they be manufacturers, spread throughout the country … I think the Americans have got to understand that nobody comes out of this thing unscathed,” Martin was quoted saying.

While the intent of Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs is for more steel and aluminum to be made in America, the problem is that the United States can’t make enough of these metals to satisfy domestic demand. According to US government figures quoted by the CBC, because US steel mills are outdated, the US imported nearly 37 million tonnes of steel last year, with about a sixth coming from Canada. The country is even more dependent on Canadian aluminum, importing over half its five million annual tonnes from Canada. With so much of these markets, then, dependent on Canadian imports, now subject to tariffs, the effect will be an increase in the prices of steel and aluminum.

In terms of ripple effects on the US economy, not only will steel and aluminum go up, but the prices of all related goods and services. That includes American-made cars, which use a lot of imported components. Those costs could reverberate through the US economy in the form of higher inflation, which could

in turn induce the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates – which would have a negative effect on stock markets, since businesses rely on low rates for borrowing and expansions. Input cost inflation accelerated to the fastest since October 2013 in May.

However Zero Hedge quoted Garfield Reynolds, a blogger for Bloomberg, noting that a trade war will damage the US, but it will be worse for US importers, which are very dependent on the US market:

“Yes, a major trade war is likely to cause damage to the U.S. economy, but a lot of that will be in the longer term. It’s going to cause significantly more pain, especially in the short term, to all those exporters Trump is targeting; and the U.S. is far and away the world’s largest net importer.”

Wider implications – China, Europe, Global

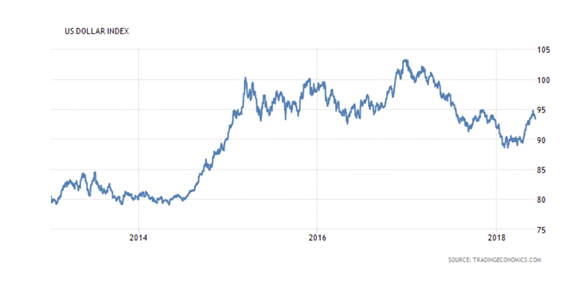

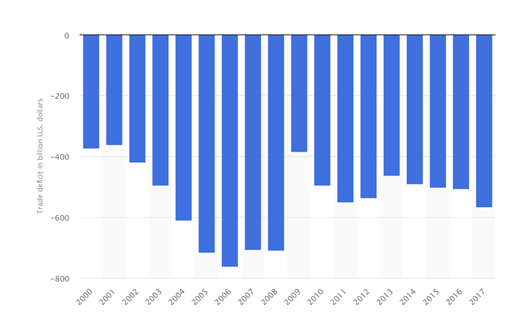

The problem for the United States is that throughout the past several years, the dollar has remained high in relation to other currencies, and that has created a large trade deficit – at last count $566 billion for 2017. It’s a problem because a trade deficit means the US imports more than it exports – meaning consumers are buying more goods and services from abroad than locally. Exporters face resistance from buyers because products priced in dollars are more expensive.

It is primarily the result of the trade deficit – and especially the trade deficit with China, $337 billion in 2017 – that has prompted the Trump Administration to engage in a series of tariff threats with its most powerful economic competitor.

But things are improving on the deficit front. According to Reuters, the US trade deficit was at a seven-month low in April due to high exports – undoubtedly helped by a low US dollar that has become a hallmark of Trump’s tenure.

So economists are puzzled as to why the Trump Administration thinks that engaging in a round of tariffs will improve the deficit; if anything, it will worsen it.

Trump claims the United States is being taken advantage of by its trading partners, but economists warn that tariffs will undercut the economy, raising prices and destroying jobs for Americans.

Economists say tariffs will do little to shrink the trade deficit, partly because of the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and the low U.S. saving rate, including a fiscal deficit that has been blown up by a $1.5 trillion tax cut package.

The politically sensitive goods trade deficit with China increased 8.1 percent to $28.0 billion in April. The United States had a $0.8 billion goods trade deficit with Canada and a $5.7 billion shortfall with Mexico. – Reuters

Over in Europe, Trump’s frosty relationships with UK Prime Minister Theresa May and Germany’s Angela Merkel have, obviously, not improved as a result of Trump’s decision not to exempt the EU from his metals tariffs. May reportedly told Trump on a phone call that tariffs on EU steel and aluminum were “unjustified and deeply disappointing”.

The European Commission has threatened counter-measures including tariffs on finished US steel products. The effect on European consumers however is expected be less from these countervailing duties than the damage done to US consumers by steel tariffs. Project Syndicate however proposes a different alternative. Rather than hitting back with more protectionism – the equivalent of “If you shoot yourself in the foot, I will do the same” the publication argues that the EU should instead impose quotas like South Korea did, thus escaping the tariffs:

The proper response to Trump’s claiming that a larger US steel industry is in the national interest should be: “Mr. President, if you insist that national security requires your country’s industry to receive lower volumes of high-quality European steel, we can help. We will organize a cartel of our producers and ask them to increase the price they charge to US consumers.”

Instead of engaging in a costly strategy of escalation with their biggest trading partner, Europe’s leaders should swallow their pride and humor Trump when he insists on running the US economy into the ground.

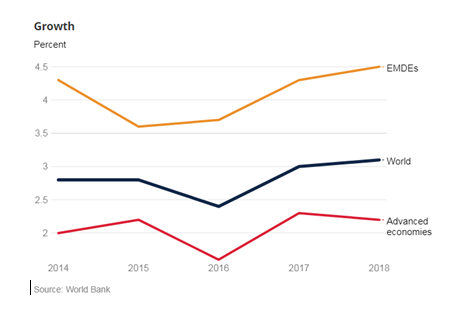

On the other hand, Wall Street banks are not yet concerned that the tariffs will do much to dampen global growth. The bigger worry seems to be what could happen next. Despite the tariff threats, the banks are “barely changing their forecasts for solid global growth this year as they estimate only modest fallout from a skirmish over commerce” according to Bloomberg.

Bloomberg Economics estimates the impact of a trade war to be around the size of Thailand’s economy – $470 billion – by 2020, if import costs to the US rise 10% and the rest of the world retaliates by the same percentage of duties.

For a trade war to really cause significant global damage, Trump would have to broaden protectionist measures to other sectors and possibly slap a blanket 20% duty on all Chinese imports according to ING via Bloomberg.

Could an economic war with China be the precursor to a military confrontation? We have written extensively on this possibility, and it remains on the radar.

Obama’s “pivot to Asia” was designed to curb Chinese territorial ambitions which include the reunification of Taiwan with China – a hornet’s nest that Trump walked into when he accepted a phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen soon after inauguration. But the pivot, to be realized through increased trade like the Trans Pacific Partnership and increasing its regional military profile, has been a failure.

The US could not prevent China from building islands and annexing 80% of the South China Sea, stop China-backed North Korea from conducting nuclear tests, or defend freedom of navigation through the $5-trillion annual trade corridor. On assuming power Trump pulled the US out of the TPP and began a dangerous war of words with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un as the reclusive nation successfully tested its first intercontinental ballistic missile capable of hitting the US mainland.

Meanwhile China continues to expand its military. In early March it was reported that China plans to boost military spending by 8.1% in 2018, compared to a 7% increase in 2017. While 2016 spending of $215 billion is about a third of that spent by the US in the same year – $611 billion – a modernization drive has accelerated in recent months. Developments include the PLA launching its first aircraft carrier, the opening of China’s first military base in Djibouti, a new J20 stealth fighter, and most worrying, the Dongfeng-41 intercontinental ballistic missile (video) capable of carrying nuclear warheads. Last summer while celebrating the 90th anniversary of the PLA, Chinese President Xi Jinping boasted that China is now capable of vanquishing all invading enemies. China has the largest ground forces in the world, bigger than those of the United States.

Many still believe that Russia, America’s former Cold War enemy, is the greatest threat to the United States. But the world has changed. Russia is a bit player in the game of geopolitics, and China is the real adversary.

Conclusion

Donald Trump said that “trade wars are good”, and his statement is about to be tested. The economic friction between the United States and its key trading partners, Canada, Mexico and Europe, has hit a new high. Such is Trump’s outlier status, the G7 Summit in Quebec City this weekend is being dubbed, “The G6 plus one”. Could it have been avoided? Certainly Trump came to power with a groundswell of opinion that was populist and nationalist, at odds with the globalist, liberal-democratic views of most G7 leaders. Part of that included a mandate to get tough with trade partners that Trump and his base feel have put the country at a disadvantage.

On the other hand, Trump’s adversaries on the trade front – and we are talking here mostly about Justin Trudeau – do not seem to have come up with a successful strategy of dealing with Trump, the deal-maker. Hectoring and calls for trans-border friendships cut little mustard with empire-builders like Trump. He knows what he wants, and those on the other side of the table need to figure out a way to give it to him, or get squashed. That may not be a very nice way of doing politics, but that is the reality of US-Canada and US-global relations right now. The sooner Trudeau and other leaders realize that the only way to meet force is with force, the better off we’ll all be.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Just read, or participate in if you wish, our free Investors forums.

Ahead of the Herd is now on Twitter.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

The post Billionaire schools teacher in NAFTA talks appeared first on MINING.com.

Source: Mining.com AL